Jacques Henri Lartigue

Early Days

Jacques Lartigue was born in 1894 in Courbevoie, just outside Paris. His family was wealthy and Jacques had a pampered childhood – easygoing tutors for his education, frequent trips to the sea or country for holidays, and endless games with his elder brother Maurice, nicknamed Zissou, and his many friends and relatives.

Jacques recognised very early on how wonderful life in general, and his in particular, was, and seems to have set out to record all the most delightful parts of it as thoroughly as he possibly could. He did this through his written journals, his paintings and his photographs.

A Christmas card in typical JHL style to his close friend Sacha Guitry, 1949

Although Lartigue made his living as a painter, and exhibited successfully throughout his life, neither his paintings nor his journals are of any great interest or merit. His photographs, however, were from the beginning quite exceptional. He had a natural ability to capture fleeting moments, if necessary creating them himself, in brilliant compositions that look utterly casual and artless.

He was also remarkably industrious, producing over a long life around 100,000 images of various sorts, many of them filed and documented in the 100 huge albums that ultimately became what is probably the finest visual autobiography ever produced. Of these, many of the early photographs, and probably a majority of the best known were originally taken in stereo.

The Stereos

Lartigue continued taking stereos until around 1929, by which time it must have been increasingly difficult to obtain the glass plates he still used. In total there are around 5,000 stereo photographs in the Lartigue archive in Paris, all on glass, all but about fifty in black and white, and all carefully preserved in individual paper envelopes in wooden storage boxes.

When, in 1976, the creation of a Fondation Lartigue was first mooted, he enthused about ‘all my treasures (albums, negatives, stereos, paintings, journals etc)’ and there are several other entries in his memoirs where he singles out the stereos for special mention. It’s absolutely clear that they were, for him, an important and quite distinct part of his collection, and one of which he was immensely fond.

The little video below shows Lartigue actually viewing his stereos, and it's obvious how absorbed he is in reliving the memories of his youth. He's using a Taxiphote, an automated slide viewer made by Jules Richard, which steps from one glass plate to the next as the handle on the side is turned...

Video awaiting HTML5 update! Real soon now...

The commentary to this video includes a couple of excerpts narrated by Lartigue himself; for non-French speakers a transcript is provided here. Several of the still photographs shown in the film are stereos (I spotted four) including of course the photo of Gabriel Voisin making the first flight over French soil, and that of Bichonnade jumping down the steps.

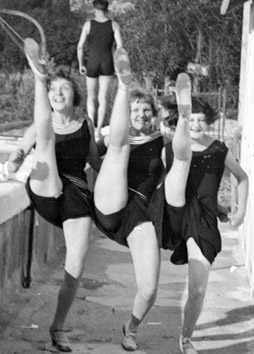

And so, it’s a great shame that when his childhood photographs were brought to the attention of the world by John Szarkowski and Richard Avedon in 1963, the fact that the images were stereo was simply ignored. Instead, prints were taken from one half of the stereo pair, and even then often very heavily cropped. The example below is extreme, but far from unique.

A chorus line - as Avedon published it

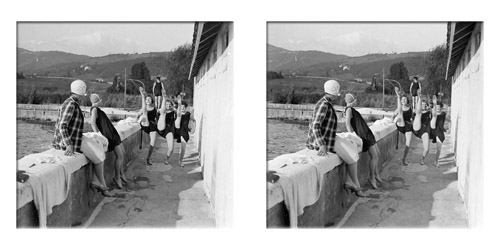

Clearly the cropped image has more impact on the screen, where the poor resolution has little consequence, but viewed in a good stereoscope the stereo image has more depth, more interest, and a richer composition.

In reading these photographs it's crucial to understand that Lartigue's main motivation was to capture the entirety of an event - he said repeatedly that he wanted to hold forever the image, the colour, the sound, the scent - everything that would enable him to relive the moment more fully. The stereo image does this incomparably better than the flat one, which is infinitely less involving.

Some more examples of Lartigue stereos.

A chorus line - as Lartigue photographed it!

Since then, the stereos have lain in the archives of the Fondation Lartigue, not entirely neglected – there was a small edition of a dozen stereos, Le troisième œil, published in 1988 – but certainly unknown to all but a very few specialists. Hidden Depths is the first and so far only publication to give a comprehensive overview of these wonderful photographs.

The Moving Finger Writes...

His discovery in the USA began around 1963, when Lartigue was already 69 years old, so only at what would be considered well past retirement age for most men did Lartigue become a professional photographer. His exhibition at the MOMA and article in Life magazine that year were only the first of a flood of books, exhibitions, articles and films drawing on his photographic collection. He continued taking professional assignments and photographing for his own amusement right up to his death in Nice in 1986 at the age of 92.

Film transcript

First commentator, reading from Lartigue's memoirs: Paris, March 1910. The air is full of warm breezes. My enormous camera is even heavier than usual on my arm. I try not to bump into it as I walk. I'm tired, but overwhelmed with pleasure at the idea of adding two or three new photos to my collection.

Pedestrians, riders, elegant carriages, and hackney cabs all descend the avenue of the Bois [de Boulogne]. It's there I lie in wait, sitting on an iron chair, my camera carefully adjusted. The distance is four to five metres, which I can estimate pretty exactly these days. The hardest part is to be precisely in focus at the very instant when she has one foot forward…

'She' – this is the lady – really stylish, or at the height of fashion, or eccentric, or maybe very pretty? – who is about to arrive. She can be seen from a long way away amongst the strollers. She approaches… I'm timid, trembling a little… Twenty metres… ten metres… eight… six… clac! The shutter of my huge camera makes so much noise that the lady jumps almost as much as me.

Lartigue: This is my first really famous photograph. My father had heard that Gabriel Voisin was going to do some tests in his glider. He took off from on high and flew for twenty metres. Even that was astonishing – it seemed extraordinary. I used to dream at night that I flew off in the air – it was really the period before aviation, when everyone was still dreaming about it.

Second commentator: Dear Lartigue. The movement, the speed, the racing cars, so many things to interest him. The beauty of the instant, the insouciance of his models, all watched like a game. Life was truly a joy.

Lartigue: On returning home, I made sketches of all the photos I had taken, before developing them, and I knew so well what I'd shot that you could recognise them, know which had gone wrong, which were good, etcetera.

Second commentator: Lartigue put the text and the sketches away in the albums that he continued to fill to the end of his life. His photos are the chronicle of a social class – wealthy, worldly, artistic – his own.

To the top